TALKING BOOKS

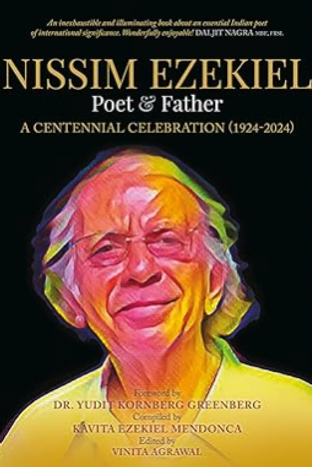

Rachna Singh, Editor, The Wise Owl talks to Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca about her book Nissim Ezekiel, Poet & Father: A Centennial Celebration (1924-2024)

Talking Books

With Kavita Ezekiel

Rachna Singh, Editor, The Wise Owl talks to Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca about her book Nissim Ezekiel, Poet & Father: A Centennial Celebration (1924-2024) of the acclaimed poet Nissim Ezekiel.

Thank you, Kavita, for talking to The Wise Owl about a book so close to your heart. Let me start by complimenting you for putting together this beautiful anthology which highlights not only the genius of Nissim Ezekiel as a poet but also his human vulnerabilities and strengths.

RS: In the book, you walk the tightrope between public remembrance and private memory. How did you navigate the emotional challenge of presenting Nissim Ezekiel the poet alongside Nissim the father—especially when these two identities sometimes collided or diverged?

KEM: Thank you, Dr. Singh, for your gracious compliment on the centennial anthology “Nissim Ezekiel Poet & Father,” compiled by me, edited by Vinita Agrawal, and published by Pippa Rann Books & Media UK. Thank you also for the opportunity to speak about this book, which is very close to my heart. It “wrote itself” because I have carried my father’s stories and memories within me for years. Though writing it was difficult, sharing the “Daddy stories and the Daddy poems” was pure joy.

I wrote the book to honor my father on his birth centenary. Born in 1924, he would have turned 100 in 2024. My primary motivation was to share our close bond rather than focus on Nissim Ezekiel’s poetic genius. As Urna Bose called it in her review, it is “A Daughter’s Love Letter to her Father, Nissim Ezekiel.” I always intended the book to center on this relationship, not to be a critical study. There already exists extensive analysis of his work online and in books on Indian Poetry in English. His vulnerabilities and strengths appear in my memoir “Waiting for Daddy” and in the poems I dedicated to him, especially “Of Flaws and Gifts,” quoted here:

I was born to a man

Who could not drive a car

Typed with two fingers

Never learned to use a computer,

(His critics got him for this one).

Not knowing what he wanted in a clothing store

Needing advice on color, style and type.

Rejoiced when he discovered the secret to boiling an egg

Simply because he thought

there was a secret to it.

Was lost when it came to banking

How many zeros in one thousand, ten thousand?

Where to sign the cheque?

Worldly affairs were beyond him

His feet firmly planted in the air.

Writing about my father came naturally; he shaped my identity long before I knew him as a poet. Public memory, especially those who speculated about his private life, is often selective and influenced by personal biases. His literary contribution, however, is widely acknowledged. These are two different aspects. The second stanza of my poem begins “I knew this man intimately,” expressing the closeness only I could truly claim. I knew his heart, while others viewed him through the lens of their own perceptions.

RS: You’ve spoken about the doubt of whether you could “do justice” to your father’s larger-than-life legacy. At what point in the process did that doubt transform, if at all, into confidence, clarity, or acceptance?

KEM: When I conceived of writing the Centennial Celebration book honouring my father, I wondered whether I could do justice to his larger-than-life legacy—both to the poetry world and to me personally. His literary reach was immense; his life touched countless others. I wanted my book to fully tribute the blessing I received as his daughter and include the blessings others received through his time, attention, and money. People still send me messages about blessings they received from him today. My doubts soon dispelled—I had no hesitation about writing, only wanting it as comprehensive as possible. My husband provided invaluable support and encouragement, giving me strength throughout the three years of writing.

Much credit goes to my sensitive editor, Vinita Agrawal, who let me write with "Words straight from my Heart," as the book says. She understood my emotions' essence and depth, acknowledging my experiences' significance in her beautiful foreword. The memoir was not finely curated to please readers but reflected the truth of my life with my father. I narrated stories of times with him and stories my mother told me—not with confidence in its negative sense, but with the honesty, humility, and grace father embodied. He often encouraged me to live by Shakespeare's Hamlet: "This above all to thine own self be true/ and it must follow as the night the day/ thou canst not then be false to any other man." Writing with integrity and honesty was important to my father, guiding both my book and my life—treasured lessons I learned from him. His passing left a huge void, and I miss him immensely.

RS: The tributes and recollections from poets like Adil Jussawala, Gieve Patel, and Sujatha Mathai also chart the parallel history of modern Indian poetry. What new facets of that literary era emerged for you while assembling these voices?

KEM: When the book idea came to me, I created an outline for its organization, which I successfully followed. One section, titled "Poets, Friends, Students and Family Remember," resulted from an email request I sent to my father's poet friends, acquaintances, and students at the international school where I taught, asking them to share memories of him. As a young girl, I had personally met many who sent tributes. It was rewarding to learn they valued my father's poetry advice, his approachability, and his willingness to help with manuscripts. My father emphasized craft, and several poets, like Menka Shivdasani, mentioned this as valuable lessons for their own writing. Many poets noted the friendships developed during meetings with my father. He helped them get books published and sometimes published them himself.

Gieve Patel says in the book: "In early years Nissim was my mentor, not only for creative writing, but also in general conversations about 'matters of the world'. Over the years this developed into friendship. There was depth and concern in this friendship." Gieve also mentions my father's friendship with poet A.K. Ramanujan: "A writer will have a range of relationships with other writers in his environment. For Nissim, A.K. Ramanujan was a near contemporary. They shared a wonderful friendship full of warmth and mutual regard."

I re-learned that poetry was a serious calling for that era's writers. They weren't writing for writing's sake but to voice what they heard and saw in their country and world. Their poetry expressed their times' attitudes and emotions. Many of those poets still write poetry and prose; though some have passed away, their work testifies to the postcolonial era. My father wrote about ordinary things in accessible language. His poetry differed from precolonial era poetry — not as a reaction to eminent poets like Rabindranath Tagore or Sarojini Naidu but simply representing a different generation speaking a different language about subjects some might consider too prosaic for poetry. Precolonial poets wrote more romantically, influenced perhaps by English romanticism.

RS: The volume interweaves your poems with your father’s, creating a quiet but powerful dialogue across generations. How did this interweaving evolve, and what did it reveal about your poetic inheritance?

KEM: The section "The Daddy Poems" opens with "Tribute to a Master Poet," containing all poems dedicated to my father. In this poem I converse with him, acknowledging his poetry mastery and asking him to guide my writing gently. In "The Black Bicycle," the concluding lines —"Sometimes, I sense his invisible hands/Guiding my words and lines"— speak of a powerful feeling I get when writing poetry, as if he is still present. The poem "My Father taught me Love" reflects emotions welling up from visiting his grave in 2005 during my India trip, captured in the second stanza:

I stood beside my father's grave

At the old Jewish cemetery across the racecourse

There was his poem about a shooting star

Engraved on it with a Star of David,

I thought I heard him recite the poem

I wept, careful not to erase the lines

His voice mellifluous and poignant

He made me fall in love with poetry.

Content-wise, the poems were easy to write, driven by love for my father and joy in our wonderful relationship. I revised them only slightly for structure that best suited expressing this love. My style choice is usually free verse, allowing 'unrestrained' thought expression. Like the memoir, words flowed spontaneously and freely. Many poems reference things my father loved, like Bombay; others spoke humorously of his strengths and flaws; others referenced songs he sang, and his love of words "my steadfast inheritance."

RS: Archival material like photographs, letters, interviews does more than document a life; it constructs a narrative of genius interlaced with vulnerability. Was there any archival discovery that particularly shifted your understanding of your father?

KEM: Choosing family photographs was challenging because many were old, especially the black-and-white ones, and some memorable photos even arrived after the book was published. Looking at these pictures makes me feel as if I’m in the presence of my parents and grandparents, reliving precious childhood moments. My father appears to me exactly as in those photos—twinkling-eyed, calm, and poetic. In every image, his personality shines through; his love for me and our family, his beautiful and positive attitude to life, and his peaceful, resilient nature in the face of life’s hurdles—a quality that has been a major lesson for me and has made “resilience’’ one of my favorite words. He never complained about anything. Truly, “a picture speaks a thousand words.’’

For the interviews, I chose those that give readers deeper insight into my close relationship with my father and his poetry. Some highlight the Jewish aspect of his work and our Bene Israeli Indian Jewish heritage. I often re-read these interviews and then return to his poems for a deeper understanding of their thought and philosophy. I included my interview with Yogesh Patel about my book, Light of The Sabbath because it reflects the love my father and I shared for Bombay and its vibrant crowds. Urna Bose’s interview brought out his personal side, including the humorous moment when he told me to change a blouse he felt was inappropriate for travelling by public transport. The memories shared by students who met him at the international school where I taught in Mussoorie were another meaningful addition. And the handwritten poem “Lost and Found in Mussoorie,” which he wrote for my students Mohana Rao and Olinda Belt, was preserved by Olinda and shared with me, allowing me to include it in the book.

RS: As you curated such a wide range of personal recollections, how did you decide what to include or leave out, especially when contributions revealed intimate or lesser-known aspects of Nissim Ezekiel?

KEM: I included personal stories and recollections in the book as they came to me naturally, especially those showing my father’s deep love. I shared how he cared for me in countless ways—some seemingly small, like bringing home a packet of peanuts each day or writing me a postcard daily when I was homesick at boarding school. I also recounted my mother’s story of their six-month stay in Leeds, where he missed his daughters so much that he choked at dinner because a marrow spoon reminded him of us. I described going with him to buy “stick” ice cream, his spending an entire month’s salary on a Philips turntable to nurture my love of music, and his carrying a double album of Handel’s Messiah all the way from Amsterdam rather than pack it and risk damage. He had bought it because I loved Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus,” which I had sung in an inter-college choir competition at St. Xavier’s College in Bombay.

There were so many more stories to tell but if they involved other people, whether family or friends of my father’s, they did not form part of the memoir. One wonderful story my father told was of running into Raj Kapoor, the legendary Bollywood actor, on a flight to New Delhi, where my father was travelling to attend a conference. Raj Kapoor, who incidentally was also in the same school as my father and a classmate of his, had the captain announce my dad’s name and ask to come to a certain seat number. To his surprise he found Raj Kapoor seated there. This story is precious but not included in the book. It is not excluded deliberately.

RS: Nissim Ezekiel is widely regarded as the Father of Modern Indian Poetry. How do you hope this centenary volume will reshape or enrich his legacy for a new generation of readers, poets, and scholars?

KEM: My hope is that the Centennial volume will add a personal dimension to Nissim Ezekiel the poet. He is used to being regarded solely as a poet by most people who knew him in a professional capacity, but in the book the poet is a father, and a man -- with all the simple and yet complex aspects of a writer fully dedicated to his calling, one who embraces his family and friends. I hope the book will enrich his legacy as a family man capable of deep love, however flawed. For those who are not acquainted with his poetry, my hope is they will be inspired to read his poems and love and admire them as previous generations have done. I am humbled and proud to learn how widely known he is in India and internationally. The title “Father of Modern Indian Poetry in English” affectionately attributed to him, places him securely in the literary history of Indian Writing in English. My father carried his fame lightly and did not place any emphasis on recognition or awards. He was fully dedicated to his passion, which was poetry. When new and upcoming Indian poets writing in English, craft their verse, they are the inheritors of a great tradition of poetry ranging from Nissim Ezekiel, Dom Moraes, Sujatha Mathai, Keki Daruwalla, Adil Jussawalla, Gieve Patel, Eunice de Souza, and others. We do not write in a vacuum. So, my hope is that the section where poets have shared their memories of my father will give them this knowledge. Though the voices of new poets are their own and reflect their times, as my poetry does too, this knowledge is essential for personal and professional awareness.

For me, personally, I carry not just pride in my father’s work, but a great responsibility in preserving his legacy.

RS: Putting this book together must have required revisiting both treasured and painful memories. When you look back now, what did the process teach you about yourself—as a daughter, a poet, and a custodian of literary legacy?

KEM: I carry with me vivid daily memories of a vibrant life with my father and our close bond, so, in that sense, I did not need to revisit the treasured moments of my childhood or later years. Putting the book together reaffirmed what I always knew — that my father and I loved each other deeply and unconditionally, the book’s central premise. Being with him was always fun, never dull, because he was a wonderful storyteller with a great sense of humor. As for painful memories, I have always placed them in context and not dwelled on them, as they did not define him; I did not gloss over them, but understood them as part of human suffering. Preserving his legacy has meant more to me than my own work. Though he was a poet of great stature, what matters most to me is that he had the gift of poetry and shared it freely with everyone he met — reaching out not only to poets but to all humanity: the crying child in a neighbouring building, the prostitute being beaten on the street, the old woman who fell outside his office, whom he waited with until the ambulance arrived and he knew she would receive proper care. He had a heart big enough to take everyone in. I try to live by the lessons he taught me about true generosity and living for others.

Writing about my life with him was intensely emotional — not only because writing is hard, but because recollection carries deep emotional weight and reminded me he is no longer here. I was often moved to tears and had to pause to absorb those memories again. I wanted to keep him alive, as he is in his poetry and in all the poems I write for him.

RS: Many of the tributes in the volume carry the weight of an era—friendships forged in the crucible of Bombay’s literary ferment. Did engaging with these voices alter your understanding of how a literary community shapes, and sometimes shelters, a poet?

KEM: My response is similar to an earlier one in which I discussed what I learned about the community of poets who regularly gathered at the P.E.N. office where my father volunteered. He welcomed everyone and, in many ways, brought this community together through their shared love of poetry. Bombay’s poets were able to meet in person, read each other’s work, and encourage one another, naturally forming close bonds. My father also travelled widely, meeting poets abroad, forging personal ties, and maintaining those connections throughout his life.

Today, things are very different: poets now meet in virtual spaces through social media, becoming part of a global community while writing from their own homes. Friendships still form this way, especially among like-minded writers. Thus, both physical and virtual literary communities continue to shape poets.

It is worth noting that Menka Shivdasani has revived the 1987 Bombay Poetry Circle, bringing together new and emerging voices for group readings. Similarly, Saranya Subramanian, founder of the Bombay Poetry Crawl, organizes readings centered on twentieth-century poets who wrote about the city in English and various Indian languages. Through active walking, participants re-trace the poet’s steps in the places described in these poems, experiencing the city in new ways. These sessions are popular.

The question of how a literary community shelters a poet is more complex. Does a poet become captive to the group’s style and expectations, or push boundaries? Most poets mentioned in the book began in the poetry circle my father belonged to, yet each developed a distinct voice – a direction he encouraged. He forged his own path early with A Time to Change, rather than follow conventional poetic styles. He was a generous mentor, and it is gratifying to read how younger poets acknowledge his influence.

Thank you for taking time out to talk with The Wise Owl. We wish you the best in all your literary and creative endeavours. Thank you for sharing personal insights about your book.

About Kavita Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca

%20-%20cropped%20(1).jpg)

Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca is a published poet and Nonfiction writer, with two collections of poetry 'Family Sunday' and other Poems, 'Light of The Sabbath' and a memoir ‘Nissim Ezekiel Poet & Father.’ She has taught English in Indian colleges and French and Spanish in private schools in India and Canada, in a teaching career spanning over four decades.

A doctorate in English literature and a former bureaucrat, Rachna Singh has authored Penny Panache (2016) Myriad Musings (2016) Financial Felicity (2017) & The Bitcoin Saga: A Mixed Montage (2019). Her book, Phoenix in Flames, is a book about eight ordinary women from different walks of life who become extraordinary on account of their fortitude & grit. She writes regularly for National Dailies and has also been reviewing books for the The Tribune for more than a decade. She runs a YouTube Channel, Kuch Tum Kaho Kuch Hum Kahein, which brings to the viewers poetry of established poets of Hindi & Urdu. She loves music and is learning to play the piano. Nurturing literature & art is her passion and to make that happen she has founded The Wise Owl, a literary & art magazine that provides a free platform for upcoming poets, writers & artists. Her latest book is Raghu Rai: Waiting for the Divine, a memoir of legendary photographer, Raghu Rai.

About Rachna Singh

Talking Books

Click Hyperlink to read other interviews